Inside MAIA, the High-Impact School Empowering Indigenous Girls in Guatemala

MAIA is transforming education for Indigenous girls in rural Guatemala, combining academic excellence, family support, and leadership to break cycles of poverty.

In the highlands of Guatemala, MAIA is quietly redefining what education can mean for Indigenous girls. Each year, the school welcomes dozens of young women from Maya communities into a rigorous academic program designed not only to change their personal trajectories, but also to impact their families and one of the country’s most underserved regions.

Education in one of Guatemala’s most unequal regions

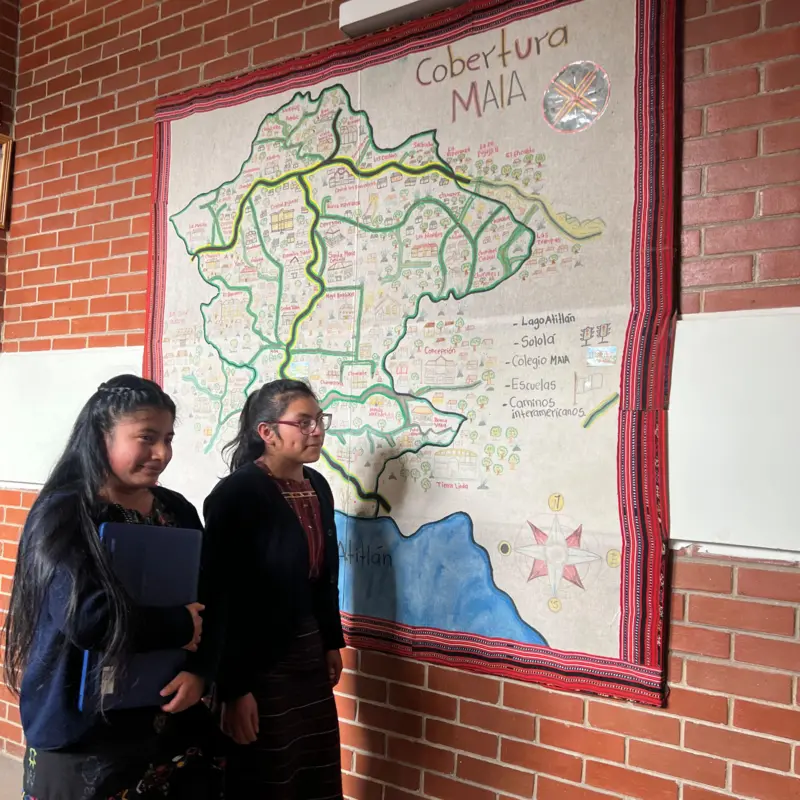

Sololá, a department overlooking Lake Atitlán and framed by volcanoes, is one of Guatemala’s most visited tourist destinations. Yet behind the postcard views, poverty remains widespread. Around 96% of the population belongs to Maya communities, and approximately 75% live on less than US$2 a day.

In this rural context, limited access to quality education has long restricted opportunities, especially for Indigenous girls. It is here, along the mountain roads outside the departmental capital, that Colegio Impacto MAIA operates as an educational oasis.

A high-performance model for Indigenous girls

MAIA currently educates more than 300 students from 40 Indigenous communities. Its campus includes classrooms, a library, dining facilities, and sports areas, supporting a comprehensive educational model that combines the national curriculum with leadership development, socio-emotional learning, and intensive family engagement.

Each student remains at MAIA for seven years, with the goal of completing at least 15 years of schooling and transitioning into university or formal employment. The outcomes are striking: MAIA students score an average of 86% in national mathematics exams, compared to a national average of 13%, and around 60% of graduates are already enrolled in higher education.

These results stand in sharp contrast to Guatemala’s broader educational indicators. The country invests just US$841 per student annually, the lowest figure among 56 countries analyzed by the Inter-American Development Bank. Only 35% of Guatemalan youth complete secondary school, a number that drops to 14.7% for Indigenous women, of whom just 1.5% reach university.

Challenging early marriage and school dropout

In rural Guatemala, early marriage and teenage pregnancy remain common. According to UNICEF, more than half of Indigenous girls become mothers before the age of 20, with many marrying at 15 or 16. MAIA was designed, in part, to interrupt this cycle.

Yazmín, a 14-year-old student from Sololá, joined MAIA after attending a public school where, she recalls, “the teaching was limited” and boys were often favored.

“You’re 15, you’re ready to get married,” she says is a common message directed at girls in her community.

When Yazmín entered MAIA, she was academically behind, struggling with reading comprehension and science. Within months, intensive leveling programs helped her close learning gaps and adapt to higher academic standards.

“Before, I was very quiet and withdrawn,” she explains. “Now I’m much more social, with my classmates and teachers.”

Education that reaches the home

MAIA’s model extends beyond the classroom. Mentors regularly visit students’ homes to work directly with families. During one such visit, Yazmín and her parents participate in a board game simulating the life choices of a Guatemalan girl: completing secondary school allows players to move forward, while early pregnancy sends them back.

For Yazmín’s parents, who married young themselves, the message is clear. “We want our daughter to graduate and become a professional,” her mother says. “The first priority is education.”

Despite ongoing economic hardship, including periods without enough food or money for transportation, the family has adopted new financial habits through MAIA’s guidance, such as saving small amounts and opening a family savings account.

Yazmín dreams of earning a scholarship abroad and eventually building a safer home for her family. Asked whether she sees opportunities within Guatemala, she answers candidly:

“It’s almost impossible. There are few opportunities and a lot of corruption.”

Guatemala ranks 146 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, a factor experts say undermines both economic growth and social mobility.

MAIA’s origins and vision

MAIA was founded in 2017 as Central America’s first school dedicated to providing elite education to Indigenous girls from rural, impoverished areas. Its origins trace back to a microcredit program for women.

“When women had access to microcredit, they invested in their families, education, housing, and health,” explains Andrea Coché, MAIA’s executive director. “We asked ourselves: how far could an Indigenous woman go if she had access to quality education? That’s how MAIA was born.”

Each year, MAIA admits around 50 girls aged 11 to 13 from communities near Sololá. The selection process lasts nearly a year and includes academic assessments, interviews, and socioeconomic evaluations. Admitted students receive full scholarships, while families commit to active participation and covering part of transportation costs.

The investment is significant: approximately US$4,000 per student per year, covering academics, leadership training, family support, nutrition, and preventive health. The school operates entirely on private donations and foundation funding.

Recognition and growing impact

Despite its young history, MAIA has gained international recognition. In 2023, it was named among the Top 10 schools worldwide by the World’s Best School Prizes and received the Zayed Sustainability Prize from the United Arab Emirates.

MAIA students have represented Guatemala at international forums from Japan to New York. The Ministry of Education has also begun exploring how some of MAIA’s practices could be adapted for public schools.

To date, around 150 students have graduated. The organization’s team, largely composed of Indigenous women, includes 15 mentors and a locally trained teaching staff that receives more than 50 hours of professional development annually.

“Our mission is to empower young Indigenous women through education to transform their lives, their communities, and their country,” Coché says. “That’s why our motto is: ‘One empowered woman is infinite impact.’”

From student to future leader

Dulce, a 17-year-old student nearing graduation, exemplifies that vision. The eldest of three siblings, she grew up helping her mother with domestic work after her father left for Guatemala City. Education, she says, became her lifeline.

In her previous public school, learning felt mechanical and repetitive. At MAIA, she experienced a profound shift.

“My way of thinking expanded,” she explains. “I became more critical. Now I analyze, I reflect.”

Educators attribute this to MAIA’s exploratory teaching methods, which emphasize problem-solving, experimentation, and real-world application. Students who arrive without basic arithmetic skills are expected to master advanced topics such as trigonometry and combinatorics.

The difference, Dulce says, is clear: “Here, exams are about thinking, not memorizing.”

MAIA also addresses topics often considered taboo, such as sexuality and reproductive rights.

“They teach us without shame and tell us to go back to our communities and show that we all have the same rights,” Dulce notes.

She plans to study accounting, with the goal of becoming an auditor. “I don’t like corruption,” she says. “I want everything to be fair and legal.”

Like many MAIA students, Dulce hopes to study abroad. After learning about the She Can scholarship program for Guatemalan women in the U.S., she felt her ambitions solidify.

“I have potential,” she concludes. “I’m not going to leave it here.”